Posted

By Greg Harman

on Wed, Aug 10, 2016 at 7:15 AM

|

| Centers for Disease Control |

The

deadliest creatures on the planet

don’t consume their prey outright. They sip them. These stealthy meals

are hardly felt at all—until the itch sets in. Then you know: Mosquito.

Mosquito-borne diseases such as West Nile, chikungunya, and

Zika—strange-sounding and remote to most American ears—are given little

attention until they rush our shores to puncture our awareness in daily

headlines and newscasts.

Until the recent rise in reports of malformed babies started generating

low-grade panic in pockets of Texas and Florida and points in between,

these diminutive bloodsuckers had been relegated largely to mere “pest”

status. Sure there have been spikes of concern with the rise and fall of

each tropical virus, but we've ignored the constant generation of

potentially crippling new diseases beyond our borders.

Our circles of compassion too often collapse at national borders,

allowing entrenched killers like malaria to continue to claim the lives

of an estimated 600,000 men, women, and children (mostly children) every

year across the planet’s tropical belt.

Today's national Zika debates over how to fund a proper response have

stuck in the miasma of our polarized politics. Historically anemic

funding of mosquito surveillance and control efforts here in Texas have

left our political leaders discussing with straight faces how best to

distribute cans of bug spray to the most at risk.

But for those who think shrunken-headed babies is the worst it can get: Prepare to be overwhelmed.

The colluding forces of poverty, globalization, and climate change have

set the stage for a rapid cascading of public-health crises in the

United States, according to one of Texas’ leading experts on tropical

disease. In other words, as-yet-unrecognized nasties are already

preparing to displace incoming Zika from the top of our news cycle.

“We’re in for a long haul of new or old infectious epidemics that are

accelerating rapidly,” Dr. Peter Hotez, dean for the National School of

Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston,

told Mark Goldberg on the “Global Dispatches” podcast earlier this year. “And we’re just not prepared.”

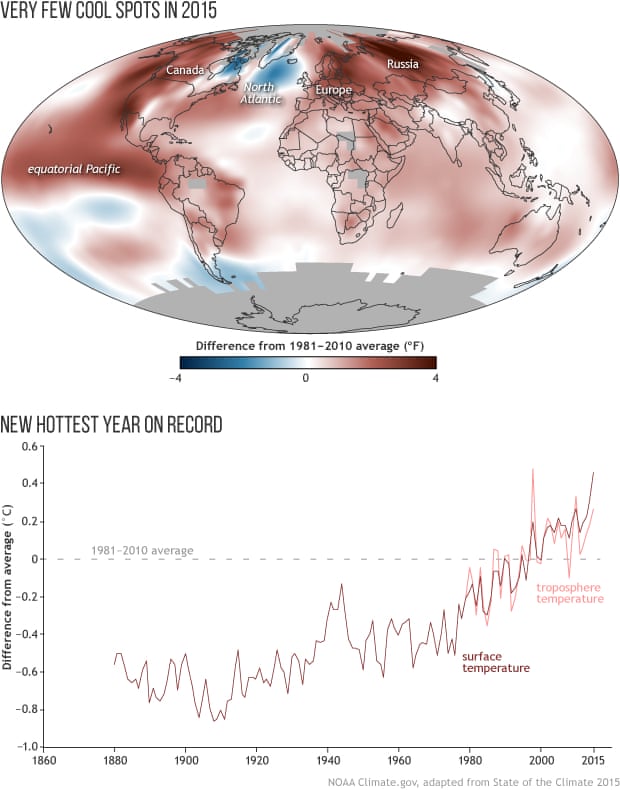

Thanks to human-caused climate change, epidemics of novel-sounding

viruses are likely to accelerate in Texas. In fact, the quickening is

already evident. Ten years after first showing its face in Texas, a West

Nile virus outbreak in 2012 resulted in an unprecedented 1,800

infections here, resulting in 89 deaths. These days, mosquito-control

yard signs staked into DFW lawns, where half of all 2012 cases occurred,

are hard to miss.

The halting reemergence of dengue, or “breakbone fever,” is again

badgering state residents, particularly in the Rio Grande Valley. During

a 2005 outbreak, the CDC estimates that one in three Brownsville-area

residents were exposed to the virus.

Sometimes mistaken for dengue in its manifestation in severe joint

pain, chikungunya (menacingly translated as: “to become contorted”)

started collecting its own domestic headlines in 2006 and 2007 and has

since been observed in most U.S. states, including Texas, though

exclusively as a travel-related import outside Florida—where Zika is

also now putting down roots.

For some time, climate change’s expansion of warmer, wetter tropical

weather across the U.S. South has been blamed for driving more tropical

disease our way. What has been missing from that analysis is

community-level research showing just how this may unfold.

That gap is beginning to be filled in thanks to the work of a Texas Tech University graduate student. As I wrote in detail for

Texas Climate News

recently, preliminary results from Kelly Neely’s work in buggy

Brownsville is demonstrating that potential disease carriers will

increase in Texas as the earth continues to warm.

That doesn’t necessarily translate into more infections; policy

responses could partially mitigate the threat. Support for the World

Health Organization’s

call for an international campaign

to fight neglected tropical diseases is vital, as is the reduction of

poverty both here and abroad that allows these killers to develop and

spread. At a federal and state level, it calls for ramping up

monitoring, prevention, and control measures.

Locally, individuals can do their part by eliminating backyard breeding habitat and patching those screen doors and windows.

More importantly, we need to do everything we can to check the

“neglected” disease march by acting aggressively to slow global warming.

Sure, we can keep the fossil-fuel throttle wide open and simply wait

for it to get too hot in Texas for the disease-carrying mosquitoes to

breed. We could reach that threshold this century, according to Neely.

That would unseat the stealthy mosquito. It could unseat us, as well.

Even after Texas' first Zika-related death this week in Houston—a child

struck with microcephaly—few are discussing Harris County's Executive

Director of Public Health Dr. Umar Shah’s admonition that this

potentially crippling wave of mosquito-borne illness is “not something

we can spray our way out of of.”

Poverty,

almost as much as the mosquitoes themselves and the warming climate

moving them deeper into the United States, is a key risk factor here in

San Antonio and around the world that few are willing to talk about.

Via

SACurrent.