By Bimbika Sijapati Basnett and Carol Colfer

“In many contexts, women are more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than men – primarily as they constitute the majority of the world’s poor and are more dependent for their livelihoods on natural resources that are threatened by climate change. “ UN Women, 2013Although neglected until recently, debates over the role of gender in climate change are slowly starting to surface. Much of the concern is in protecting the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable women and men who depend on climate-sensitive natural resources.

Most of the organizations working on gender and climate change start with a premise similar to the quotation above from UN Women. Women are said to be more dependent on natural resources and therefore, more susceptible to climate variabilities. Women are also portrayed as more politically and socially marginalized compared to their male counterparts and therefore, less able to influence policies and decisions.

At the same time, women are seen as possessing knowledge and skills that can be used to both adapt to climate change and mitigate its effects. The implication then is that women are a strange combination of “victims” and “agents” of change in climate change and integrating women in climate change policies and interventions is considered “smart economics”.

Are these ideas backed up by evidence?

In a 2011 study in Global Environmental Change, Seema Arora-Jonsson, associate professor at the Swedish Life Sciences University investigates the empirical foundation underpinning calls for integrating gender in climate change. She says that such calls are often based on the assumption that women are the poorest of the poor and that they have a higher mortality in climate change induced natural disasters.

Figures are often used to back up these claims – women are said to constitute 70% of the poor and to be 14 times more likely to die of natural disasters. But, she says, the former frequently cited ‘fact’ was based only on a qualitative (back of the envelope) estimate. It was then repeated endlessly.

There are significant difficulties generating such figures accurately given the lack of data. Most household surveys in developing countries do not collect data on individual or joint ownership of assets and where they do, data is coded in a way that the sex of the co-owners is indistinguishable.

Gender and poverty are two separate issues

Gender and poverty are two separate issues and cannot be conflated says Cecile Jackson from the University of East Anglia. Gender disadvantage in the form of female infanticide in India, for instance, is predominantly an urban, middle and upper-caste based phenomenon.

There is an assumption that women are the poorest of the poor, based on differences in relative levels of poverty between female and male-headed households. The rise in female-headed households is related to a range of factors such as women’s unwillingness to accept unjust marital relations, growing mobility of women and men in search of employment opportunities within and outside their homesteads and other factors.

A number of studies have also pointed to the importance of distinguishing between ‘de jure’ and ‘de facto’ headship, the latter where the principal male is temporarily away.

For example, in Nepal, de facto female-headed households have risen dramatically since the early 2000s due to significant increases in men moving to the Gulf and Southeast Asia for employment. These households are likely to be in a better economic position because of a regular flow of remittances in comparison to their male-headed counterparts without a household member working overseas.

Ownerships of assets better predicts poverty

While there remains considerable debate over how to measure poverty, the International Food Policy Research Institute’s (IFPRI) work on gender and assets has convincingly shown that assets are a better predictor of structural poverty than income.

From a gender perspective, ownership of assets is an integral component of women’s bargaining power within and outside their households and their fall-back position in the case of marital breakdown.

Drawing on nationally representative household surveys (such as the Living Standards Measurement Study) in twenty six countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, economist Carmen Diana Deere and her colleagues at the University of Florida conclude that comparing levels of poverty between male and female headed households “exaggerates the asset poverty of women”.

This is because current analysis in household headship does not take into account that women in male-headed households can be owners or co-owners of assets (such as of homes, lands or businesses) with their husbands or partners.

Stop victimizing

The current argument for integrating women in climate change is based on tenuous assumptions and weak empirical evidence about women’s victimhood. Instead, policies and projects aimed at addressing climate change and increasing gender equity need to be based on greater analysis and acknowledgement of the social, economic and political realities that underpin the lives of women and men in the context of climate change.

Instead of regarding them simply as victims, we need to recognize that women are actors with their own interests and have varying abilities to translate their interests into action. Such a shift in thinking will help to strengthen women’s self confidence and thereby catalyze their energies and creativity in solving climate change issues.

Source: http://www.forestsclimatechange.org % here

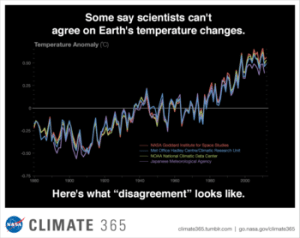

As heat records continue to pile up, climate change deniers will have an increasingly tough time explaining their position.

As heat records continue to pile up, climate change deniers will have an increasingly tough time explaining their position.  The

drought in California is the worst in over 1200 years. Record wildfires

were experienced in Washington State including the largest wildfire in

the state’s history with 400 square miles of land burned and 300

structures lost. Major floods and hurricanes occurred throughout the

world. 2015 promises more of the same.

The

drought in California is the worst in over 1200 years. Record wildfires

were experienced in Washington State including the largest wildfire in

the state’s history with 400 square miles of land burned and 300

structures lost. Major floods and hurricanes occurred throughout the

world. 2015 promises more of the same.