Beware the return of the world’s most powerful climatic phenomenon

IT IS a long way from the western Pacific Ocean to the flooded streets of Buenos Aires where, this month, the city’s Good Samaritans have been distributing food and candles by kayak after some unseasonably heavy rain. But there is a link. Its name is El Niño.

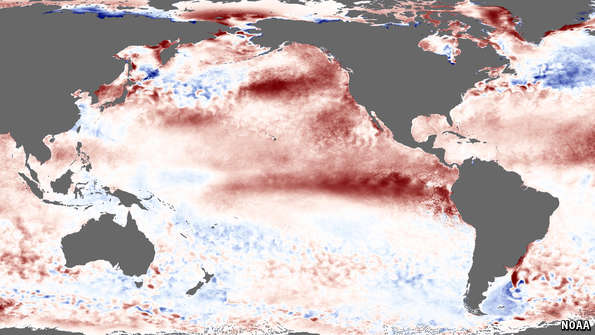

El Niño (Spanish for “The Boy”) is a Pacific-wide phenomenon that has global consequences. A Niño happens when warm water that has accumulated on the west side of the Pacific floods eastward with the abatement of the westerly trade winds which penned it up. (The long, dark equatorial streak on the map above, which shows sea-surface temperatures for August 10th-16th, indicates this.) The trade winds, and their decrease or reversal, are part of a cycle called ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation—see article).

The consequences of this phase of ENSO include heavy rain in south-eastern South America, western North America and eastern Africa, and drought in Australia, India and Indonesia. Another consequence, around Christmastide, is the sudden disappearance of the food supply of the Pacific anchoveta—and thus of the livelihoods of Peruvian fishermen. It was these fishermen who gave the phenomenon its name, the Boy in question being the young Jesus Christ.

El Niño-watchers at America’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) noted worrisome ENSO-related changes in both sea temperature and air pressure earlier this year. They declared the return of the Boy in March. Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology decided to wait until May. Such forecasts can be wrong. Despite signs of the phenomenon last year, no monstrous event actually emerged. But during July the surface temperature of the central equatorial Pacific was almost 1°C higher than expected, and its equivalent in the eastern Pacific was more than 2°C above expectations. Among other things, that puts the temperatures in these areas well above the 26.5°C minimum needed for the formation of tropical storms. Right on cue, on July 12th, six such cyclones spun in the Pacific—more than on any previous day in over four decades.

Article in full here via The Economist.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário