This is the age of the megacity: urban areas with populations of

more than 10 million are on the rise. And as more and more people

flock to the city, rising temperatures and heatwaves are likely to

make life difficult in urban centres, scientists say.

Some highlights from this week's European Geosciences Union

(EGU) conference explain why cities are so vulnerable - and offer

suggestions for how citizens can ease the pressure.

Population explosion

By 2050, the global population is expected to

grow to 9.6 billion, up from one billion at the start of the

Industrial Revolution. Of the growing population, 75 per cent are

expected to live in cities.

Rapid population growth and urbanisation are having profound

impacts on our environment. As John Burrows, professor of

atmospheric physics and chemistry at the University of Bremen, told

journalists at the European Geosciences Union (EGU) conference this

morning:

"Humans are no longer a passenger on

this planet, we're driving it."

As more people are moving into cities, urban areas becoming more

crowded, and at the same time they're expanding outwards.

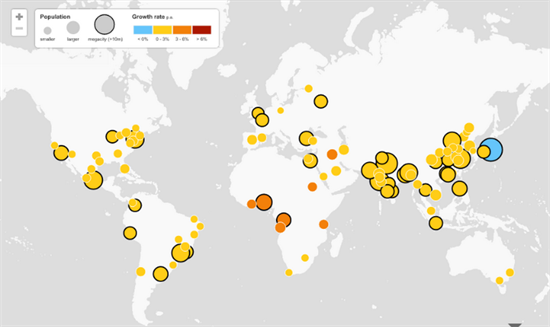

As this Guardian interactive

explains, 23 cities are currently classed as megacities,

including New York, Sao Paulo, Dakar and Tokyo. That means they

have a population of more than 10 million.

And that number is growing. By 2025, the United Nations predicts

there will be 37 in total.

|

| United Nations research suggests there will be 37 megacities by 2025. Source: Guardian Interactive. |

People, buildings and industry are densely packed in cities. Heat gets trapped, meaning the ambient temperature is often higher than the immediate surroundings. This is known as the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect, and scientists expect it to intensify as the climate warms further.

Not all towns and cities are the same. Research by Bin Zhou from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Research finds the summer UHI effect is closely related to the size of the city. But other factors such as the layout, how much vegetation exists and the proximity of the city to the sea (where breezes have a cooling effect) all affect how big the UHI is, other research suggests.

By Roz Pidcock

Read more @ The Carbon Brief

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário